Mashing

Assuming we see getting all the ingredients as step zero, the fun

starts with step one: the mash. So we haven't even

started yet and we can already raise a first point. Where do all

these crazy brewing terms come from? Well, I have no idea but I

always suspected that beer brewers were a little drunk and simply

bastardized common words. Just stand in from of a mirror, pull a

silly face and say the words mash and wort 20 times. Now do it after

a few beers. You'll see what I mean.

The idea behind the mash is to extract sugars from fermentables that

we can later turn into alcohol. For today's homebrewers there are

two and half ways to handle this step. Firstly, we're going to look

at using malt extracts which were created by

someone else. Think of it as outsourcing the first step so we don't

have to start with a lot of equipment. Using extracts, everybody can

make beer on the kitchen stove. Secondly, we'll look at

whole grain mashing which is what beer makers have

been doing for centuries. This process is a little more complex and

requires more equipment.

Extract brewing

As stated above, extract brewing is an entry level technique to

allow as many people as possible to start with the hobby. Two types

of extracts can be purchased from a homebrew store and often they

sell them in kits to include the other ingredients as well. In both

cases someone else has extracted sugars from fermentables and we

just simply add them to water. Dry Malt Extract or DME comes in

powder form and Liquid Malt Extract or LME comes as the name

suggests in liquid form.

I've used both types and I have a preference for DME since it can be

bought in a very light color and it doesn't have that caramel taste

that I so often had with LME. Please note that others swear by LME

but they may be making a different style of beer. For my Belgian

style Tripels, Witbier and Pale Ales, light DME was better.

Using an extract massively simplifies the early steps (as we will

see later). In the end, mashing is as simple as dissolving, mixing

and starting the boil.

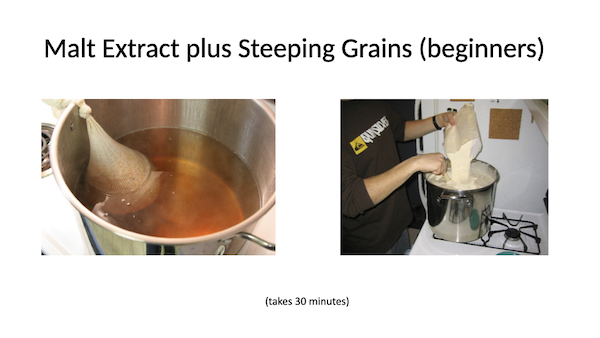

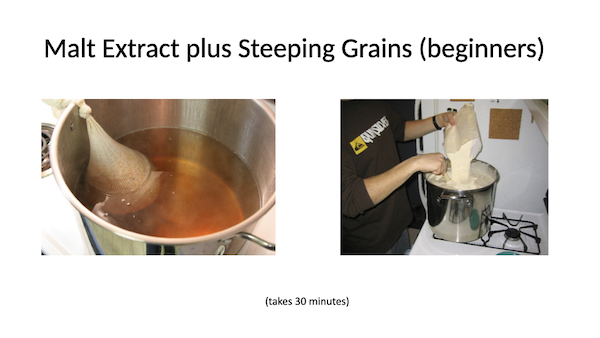

Earlier I stated there were two and a half ways of mashing and I was

referring to a hybrid approach between extract and

whole grain brewing. Often kits have a small amount of

crushed grain that will be steeped in water of a certain temperature

(often around 155F) for 30 minutes or so. You only need a bag for

this and it's basically the same idea as steeping thee. The benefit

of that is that you can add interesting flavors and it gives the

sensation that the beer is more fresh and rich. The entire time I

did extract brewing, I used this style.

So if you are only interested in extract brewing, you can skip the

rest of this section and go straight to the

boiling process. In fact,

if you never brewed before, I recommend you do this as the next part

of this section is probably the most complicating part of beer

making. Once you understand the whole process, come back here and

learn how it's done for real.

Fermentables

All beer brewing is based on converting sugars into alcohol so let's

have a look at where these sugars come from. Firstly, there are the

traditional fermentables like barley, wheat and rye. Most beers are

made from sugars extracted from these grains.

It is also possible to use other sources for our sugars and these

are typically added to the grains above for flavor (think of fruity

beers like Kriek Lambic) or to make stronger beers (like adding beet

sugar for strong Abbey Ales). It is also possible to make alcoholic

beverages by just using these fermentables. Think of wine or hard

seltzers but these are obviously not

beers.

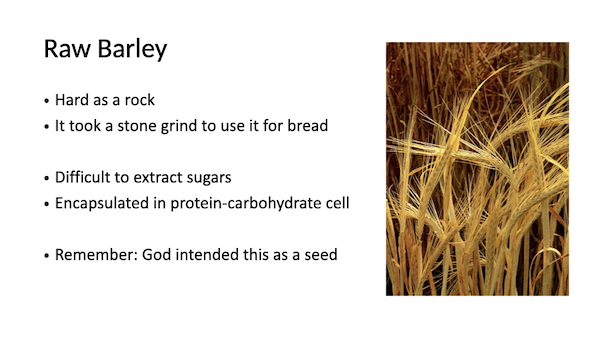

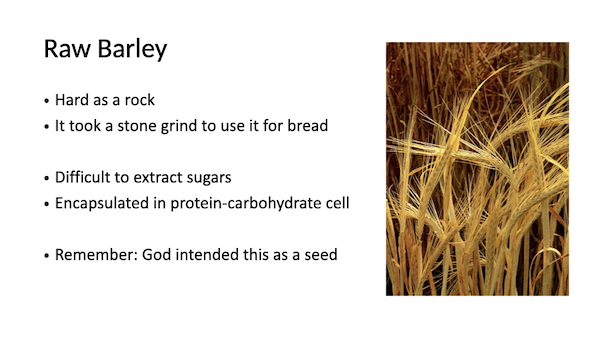

Malting Barley

So how do we extract sugars from grain? Well, let's start with

Barley. It turns out that it's not easy to get the sugars released

from it. The slide below sums up our problem.

So to get to the sugars, a three step process called

malting is used. Firstly, the grains are steeped to

soften them up and then a germination process is started to open

them up. Obviously we don't want to grow fields of barley at this

point so we need to stop the process. Through a drying/roasting

process, the germination process is halted and the barley is now

ready for our brewing process.

Since the barley is roasted at the end of the malting process,

different roasting times and temperatures will result in different

products just like with coffee. Malts can therefore be roasted

lightly to dark which results in a different color and flavor.

Lighter beers typically uses malts from a lighter roast and darker

beers like stouts use a darker roast.

The level to which the malt is roasted is measured in

degrees lovibond

which measures the color of the resulting beer. Lighter beers like

lagers have a low number and darker beers like stouts have a higher

number.

Some of you might already be getting scared at this but but don't

fear, the malting process is typically done in large industrial

facilities. As home brewers, we simply buy the malt in the color we

want for our recipes. In fact, I don't know of a single home brewer

that malts his/her own grain even though I assume they exist.

Beer making supply stores typically offer up a wide variety of malts

and they typically come whole or crushed. I always buy mine crushed

as I don't own a malt crusher. My local store crushes the malt to my

liking and since I use it immediately, it's just as fresh as when I

would do it myself. Many home brewers however crush their own grain

as they want full control over the process (e.g. determine

coarseness).

Extracting Sugars

Now we're finally ready to extract those sugars from our malt. I'll

first explain the manual way and later explain how we can simplify

and/or automate this process.

Sugar extraction is the process of creating

sweet wort, which is typically a three step affair:

mashing to extract the sugars,

lautering to filter the wort and

sparging to get the last sugars from the grain.

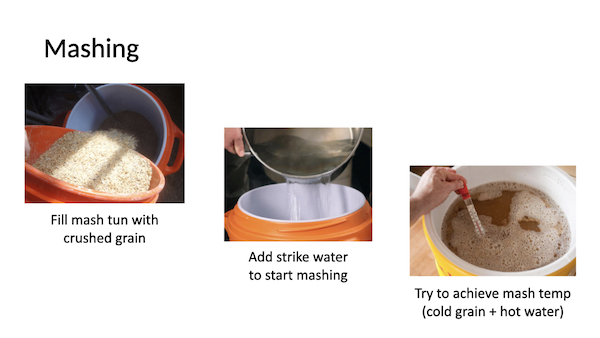

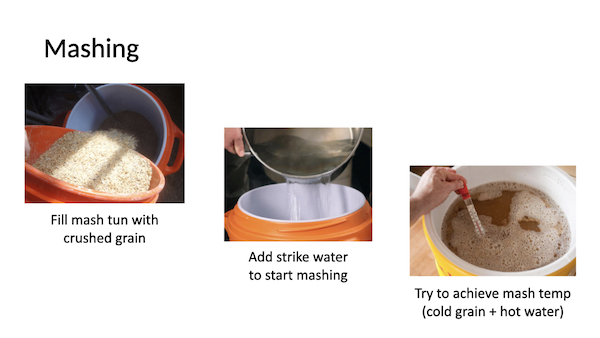

Mashing is where we add warm strike water to the

crushed grain which is typically at room temperature. A little bit

of math is involved here as we want the combination of warm water

and cool grain to end up at the desired mash temperature. Luckily

these days there are great apps and websites that will do these

calculations for us. The temperature of the mash is important is it

determines how the sugars are extracted and what kind of sugars we

want. The science behind this is way beyond a Brewing 101 but at the

bottom of this page is a reference to a book that explains it all.

Warning thougH: there is some serious chemistry and biology involved

here.

Throughout the mashing process (or just at the end), we use the

grain bed to filter the sweet wort which is called

lautering. Lautering is done by circulating liquid

from the bottom of the mash tun to the top either

by hand or with a pump. Mash tuns typically have false bottoms to

support this and the grain bed does a great job at catching the

small particles that resulted from crushing the grain.

Once the mashing and lautering processes are completed, it is time

to separate the sweet wort from the grain and rinse the grain to

extracted every last bit of sugar. This is called

sparging and people have come up with a lot of ways

to do this. Sparging is typically done with water warmer than the

wort.

As you can see later, if you automate the mashing and lautering

process, there are plenty of people who argue that sparging is not

even required.

So if this wasn't obvious before, beer brewing is a religion and

everybody has their own opinion. I can guarantee you that posting

this simple 101 online will draw fire from the high priests of home

brewing. Don't be discouraged by these types though, you'll soon be

making better beer than they are.

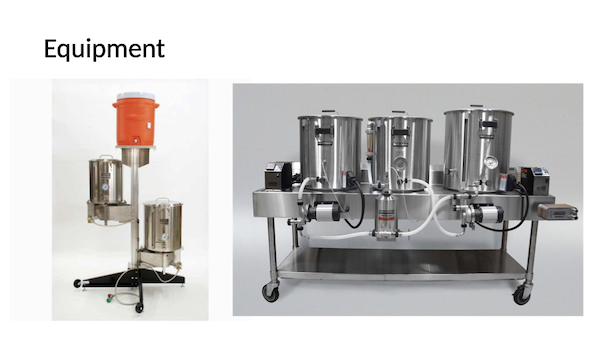

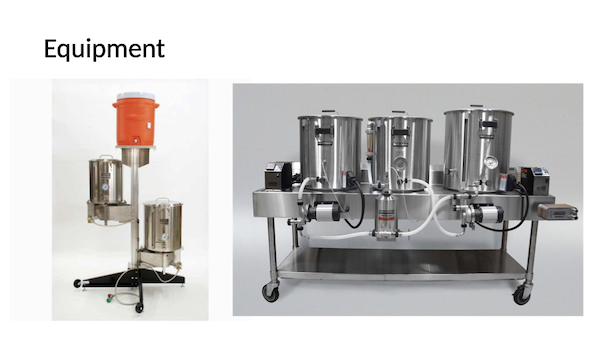

Mashing Equipment

As you figured out, extracting sugars is a complicated process and

home brewer ingenuity has gone crazy over the years on how to do

this on a small scale and within budget. Firstly, there the people

(including me) that used gravity and manual labor to move the wort

through the process. This makes for a long brew day with a lot of

steps and heavy lifting. As a beer drinker, I alway though this was

a good idea as I was burning some of the calories I would consume

later.

Secondly, there are people who invest a lot of money and create a

mini version of a commercial brewery with stainless steel vessels

and pumps. Both this and the manual/gravity method will work but in

both cases, you have a lot of stuff to clean at the end of your brew

day. Again, this could be a positive as you're burn calories before

you consume them.

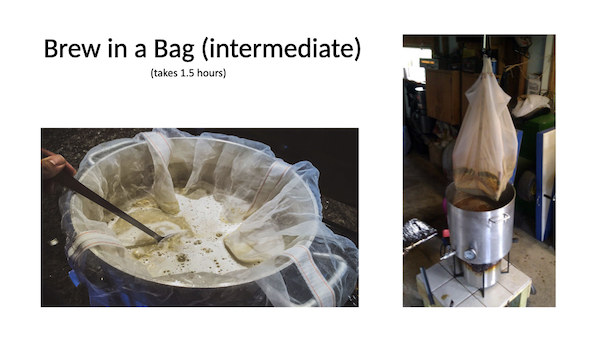

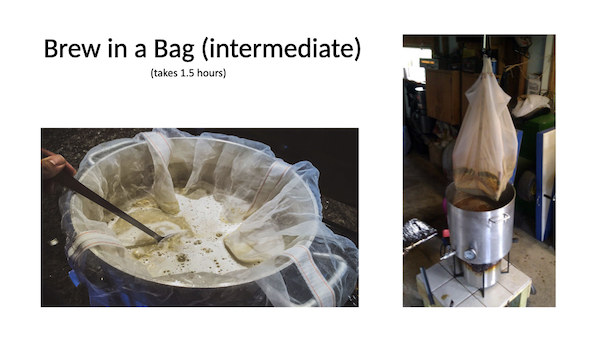

In my case, I took an intermediate step and went from extract

brewing to brew in a bag. With this technique, you

are extracting sugars from your grain in the same vessel that you

use for the boil. The idea is really simple as you steep your grains

in a large brew pot just like steeping thee for the entire city of

London in one go (slight exaggeration).

This step allowed me to move to whole grain brewing without a great

investment (I already had a fancy brew pot for extract brewing) and

I felt like I was moving forward. My only negative was that my sugar

extraction efficiency was poor and my beers weren't measuring up to

the Belgians I was trying to recreate.

Given that "brew in a bag" was not going to get me to make

my favorite Abbey Brews, I did go down the manual/gravity mashing

route described above for a while. Unfortunately my patience and

endurance were not compatible with this approach and my beer quality

became inconsistent and unpredictable. It was time to either go back

to extract brewing (nothing wrong with that as I managed to make

some great beers using this technique) or to find a different way.

The answer turned out to be an electric all-in-one brewing system

that automates the mashing. lautering and boiling process. This is

also a significant investment but it simplifies the brewing process

and it offers a repeatable process that creates a more consistent

outcome. So I've invested in a Braumeister and never looked back.

Multi-Step Infusion

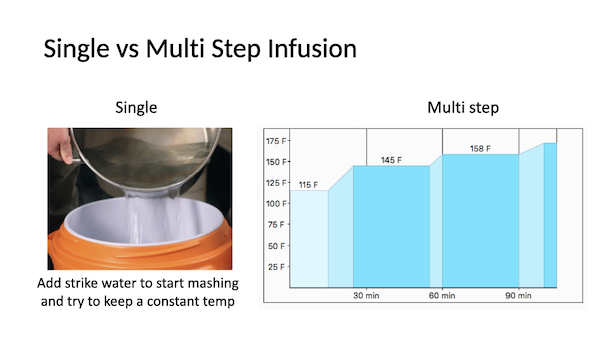

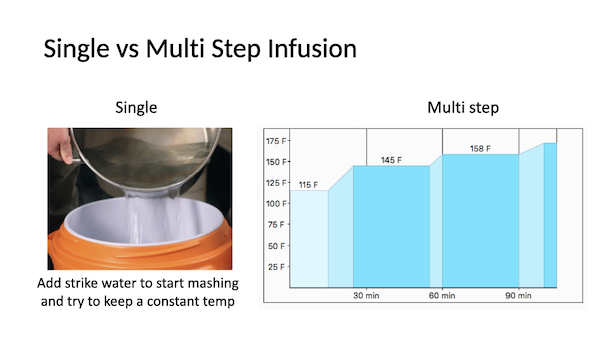

When you use the manual mashing process, it can be very hard to keep

the temperatures at the right level. This is why I always did single

step infusions where you try to keep the mashing temperature as

constant as possible during the entire mashing process.

Once you move to an all electric system, you can move to a

multi-step infusion process where you use different temperatures to

extract the sugars. This is the process used by commercial beer

brewers as it allows them to extract more and the right kind of

sugars to achieve the effect they are after. If you are interest in

this, the links at the bottom of this page will recommend books and

web site that will explain chemical processes like the acid rest,

protein rest, starch conversion or saccharification and diacetyl

rest. This stuff will make your brain hurt long before you have a

hangover.

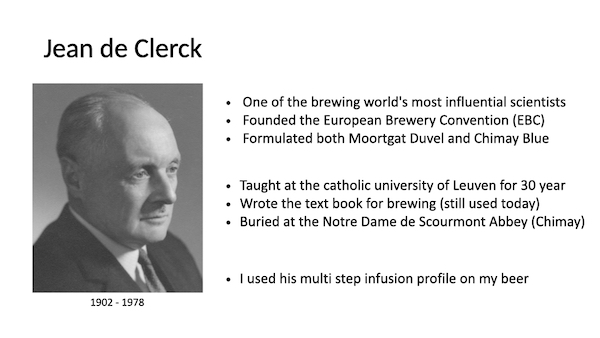

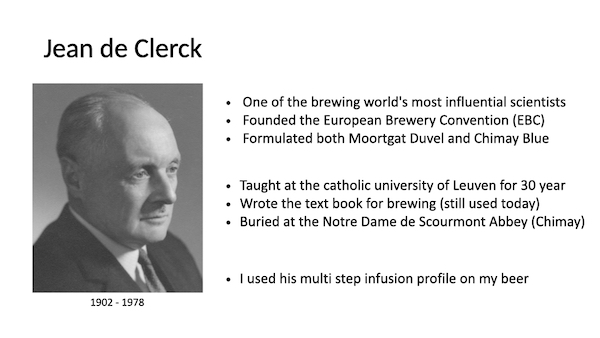

As I'm interested in Belgian Ales, I quickly learned of a man called

Jean de Clerck who was and probably still is one of the most

influential beer brewing scientist. So until I fully understand the

chemistry behind the mashing processes, I've adopted his

mash schedule for a number of my Belgian recipes.

If you made it to this part of this tutorail, you deserve a medal.

The mashing process to extract sugars and create sweet wort, is the

most complicated part of beer brewing. you can see why beginners

start with extract brewing. I must say however that by investing in

electric brewing, I have simplified the process as well and the

automation allows for very consistent products. If I could only

understand all the chemistry behind all of this so I could reason an

outcome rather than rely on trial and error.